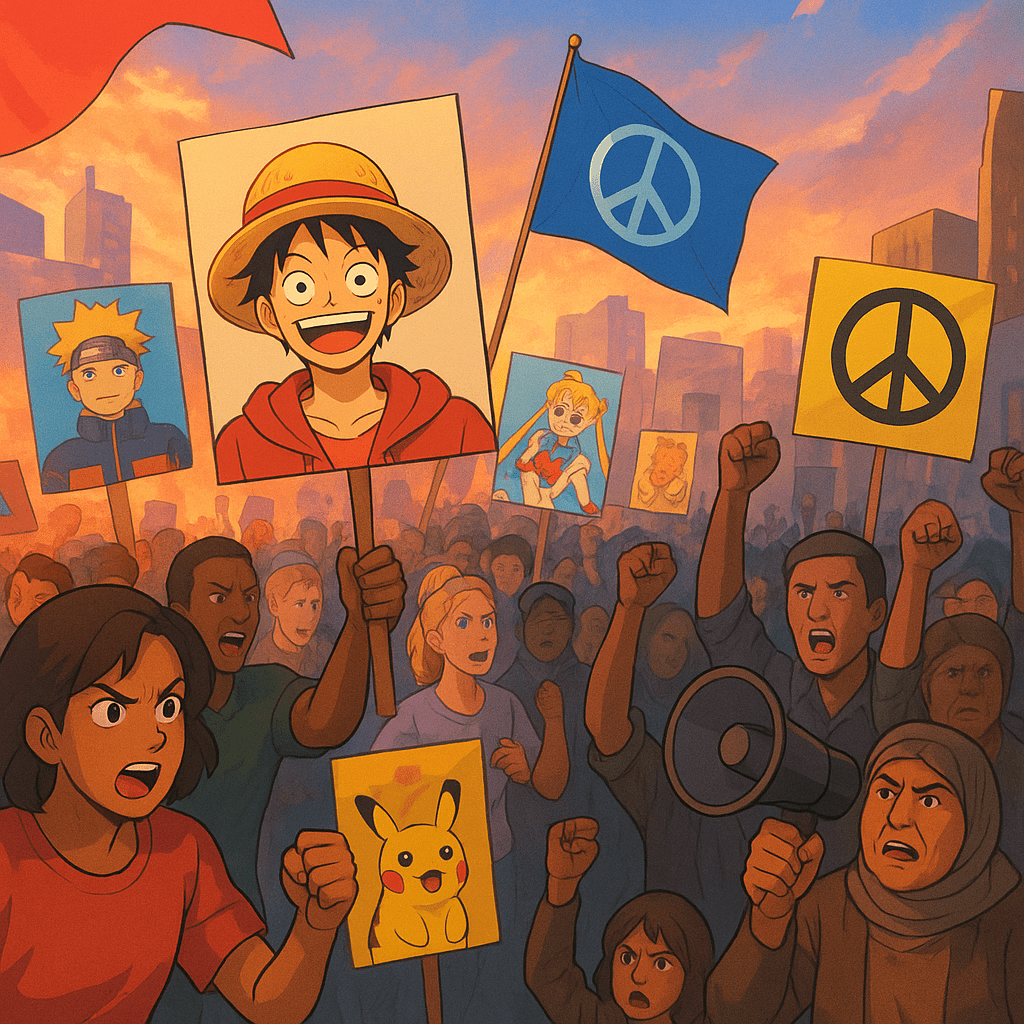

From Luffy to Pikachu — How Anime Became a Global Language of Protest

When a cartoon pirate skull and a yellow electric mouse show up in the front lines of mass demonstrations, you know something cultural is happening. Over the last few years anime imagery, from One Piece’s straw-hat Jolly Roger to Chile’s now-iconic “Aunt Pikachu” has been adopted by protesters across continents as an instantly recognizable, oddly powerful symbol of dissent. This isn’t cosplay flash, it’s a new kind of protest shorthand that fuses nostalgia, pop culture, and political messaging in one meme ready package.

The reason I brought up this matter today is young demonstrators in Indonesia and Nepal have been waving the One Piece “straw hat” pirate flag as a symbol of resistance and liberation, turning a fictional pirate emblem into a real-world protest banner. The symbol’s use has spread to rallies in multiple countries and even triggered official pushback in some places. That’s not all, In Chile, a protester nicknamed “Tía Pikachu” (Aunt Pikachu) donned a Pikachu costume during anti-austerity demonstrations and later became a viral and politically consequential figure, ultimately being elected to a constitutional body. Pikachu’s costume became shorthand for joy, resilience, and irreverence in the streets.

So why anime imagery traveling so well in protests

First thing that come to mind is Instant recognizability and emotional resonance of anime characters. Characters like Luffy or Pikachu are global brand icons. When crowds wave a straw-hat skull, the image creates fast rebellion, mischief, a desire for freedom .That speed matters on noisy streets. And a bright costume or a bold flag is made to be filmed and shared. Videos of Aunt Pikachu or crowds with the Straw Hat flag spread quickly on X/TikTok/Instagram, amplifying local protests to international audiences. The visual simplicity plus internet virality equals global reach. Unlike overt political symbols tied to a party or ideology, anime images can be framed as “pop culture”, which sometimes makes them harder for authorities to censor without looking absurd. That ambiguity can be protective; it also gives protesters flexibility in messaging. Emotional storytelling is a major factor. Many anime center on underdogs fighting corrupt power structures. That storyline maps neatly onto young people’s grievances about corruption, inequality, and lack of opportunity, so the imagery carries narrative weight beyond being “cute.”

Governments reactions in this case have varied. In some cases authorities have treated anime flags and costumes as harmless or absurd; elsewhere, officials have tried to suppress or delegitimize them. Indonesia’s use of the Straw Hat flag, for example, provoked heated commentary and some confiscations, with officials warning against acts they labeled “unpatriotic.” Human rights groups criticized such crackdowns, arguing they suppressed peaceful expression. There are reasons for it being a pushback. A colourful, nontraditional symbol can be unnerving for authorities. It’s low-cost to adopt, hard to regulate, and effective at generating sympathetic global coverage when protesters are met with force. That combination makes pop-culture symbols surprisingly potent.

This trend isn’t just viral content. In Chile, the protester who became “Tía Pikachu” transcended meme status and entered formal politics, showing how street-level symbolism can translate to political capital. In Asia, One Piece flags became rallying icons for Gen Z activists demanding reforms, sometimes amid violent clashes, demonstrating how a symbol can unify diverse grievances into a single visible banner. These examples are a loop like pop-culture symbolism drives visibility → visibility attracts media and solidarity → attention can yield political opportunities or protective scrutiny.

These protest symbols carry some risks to that should be carefully considered. Dilution of meaning can be a big concern. As a symbol spreads, its message can fragment. A flag that once signaled anti-corruption might be rebranded, commercialized, or mocked. The more mainstream it becomes, the less raw its political edge may be. Then some politicians or brands might appropriate the imagery to appear “youth-friendly” without delivering real change. That superficial embracing can blunt grassroots pressure. There are also some legal risk for protesters. In some jurisdictions, authorities could interpret nontraditional symbols as subversive, giving them cause to arrest or charge demonstrators, especially if the images are framed as foreign or “anti-national.” Amnesty and civil-rights groups have warned about overreach in some recent crackdowns.

But above all, when teenagers in Jakarta or Kathmandu lift a straw-hat skull skyward, or when a cheerful Pikachu joins a chant in Santiago, they’re doing more than posting a meme. They’re representing global stories of struggle and hope to express local anger, and they’re using the most portable language of our era, which are visuals that travel faster than words. Whether those symbols become permanent fixtures of protest culture or just a striking chapter in the history of modern dissent one thing is clear: in the age of viral media, a cartoon can be a powerful political factor.

I love the idea of anime imagery acting as shorthand for protest. It’s like a new language of dissent that brings both a sense of nostalgia and relevance to the struggles people face. I’m especially intrigued by how Pikachu, of all characters, became such a powerful symbol of joy and resistance in Chile.