Why Were 1980s–90s Anime So Obsessed With Cyberpunk

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, anime entered a creative era dominated by neon skylines, cyborg bodies, oppressive megacities, and the anxieties of a rapidly evolving world. This surge in cyberpunk and futuristic settings wasn’t accidental — it emerged from Japan’s unique position at the crossroads of explosive technological growth, economic volatility, and lingering post-war trauma. As global cyberpunk literature and film began redefining speculative fiction, Japanese animators and storytellers absorbed those ideas and reshaped them through their own cultural lens, producing some of the most iconic dystopian worlds in animation history. Here are some of the possible reason as to why anime from the 80s-90s went full on future mode.

Key reasons

- Japan’s economic boom + cultural anxiety about its fallout

The bubble economy of the 1980s created unprecedented wealth, hyper-urbanization, and a futuristic cityscape — but that very boom produced anxieties about what modernity and runaway capitalism were doing to society. Anime used dystopian futures to process those contradictions (glossy tech vs. social cost). - Post-war and nuclear trauma → dystopian imagination

Japan’s post-war experience (nuclear trauma, rapid modernization) fed a cultural tendency to envision apocalyptic or traumatised futures. Cyberpunk’s damaged cities and body/identity crises were a natural outlet for those deeper fears. - Direct influence from Western cyberpunk (Gibson, Blade Runner) and international comics

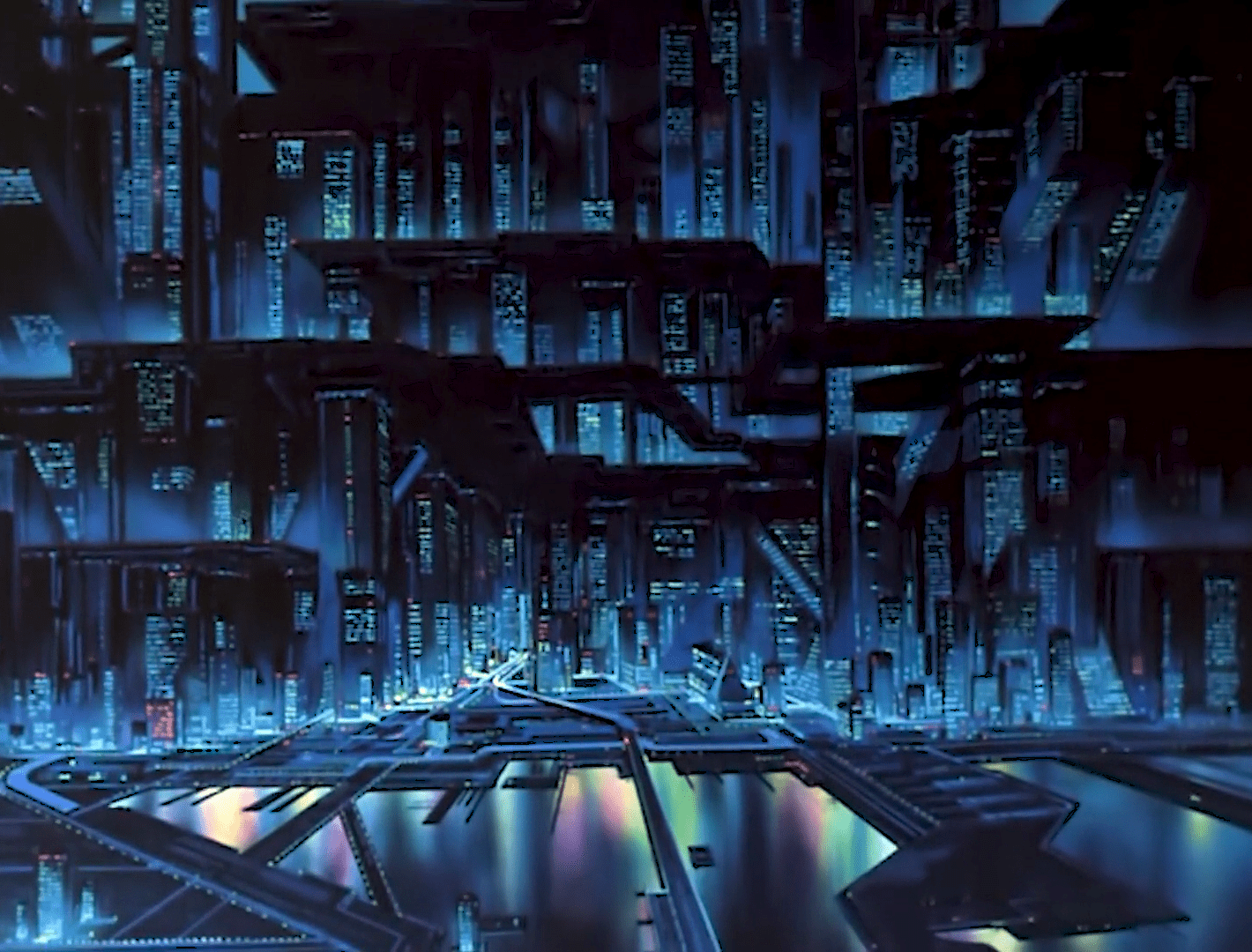

William Gibson’s Neuromancer and Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (and European bandes dessinées like Métal Hurlant) shaped a global aesthetic — Japanese creators read these works and adapted the ideas to Tokyo’s skyline and local concerns, producing a distinctly Japanese cyberpunk. - Akira and a new visual/production standard — proof of concept

Katsuhiro Ōtomo’s Akira (1988) proved that anime could depict colossal, gritty futures with cinematic scale and adult themes. Its international success validated cyberpunk as both an aesthetic and a commercially viable route for anime creators. - Philosophical/technological questions matched to youth culture

The 80s–90s rise of personal computing, networks, and body-mod tech made questions about identity, consciousness, and “what it means to be human” urgent — perfect fuel for stories about cyborgs, hacking, and fragmented selves. Anime creators used these to explore posthuman anxieties in ways other media were only beginning to. - Market and demographic shifts — older teen / young adult audiences

As manga/anime publishing matured, creators and studios targeted older teens and young adults; darker, more complex cyberpunk narratives fit that audience and allowed riskier content (moral ambiguity, graphic imagery, political themes). - Aesthetic fit: neon megacities, rain, chrome, and the “low-life/high-tech” vibe

Tokyo’s dense urban visuals translated perfectly to cyberpunk’s signature look — neon signs, cramped alleys, monolithic corporations — so the setting became both familiar and uncanny, making it easy for creators to localize cyberpunk aesthetics.

Quick recommendation chart

- Akira

- Ghost in the Shell (1995)

- Bubblegum Crisis

- Megazone 23

- Serial Experiments Lain

- Cyber City Oedo 808

- Patlabor (especially the movies/OVA tone)

- Battle Angel Alita (OVA / Gunnm adaptations)

- Cowboy Bebop

- Armitage III

- Trigun

Final Thoughts

The 80s–90s cyberpunk wave in anime wasn’t just a fad — it was a cultural reaction: Japan looked at its gleaming future and asked “what will we become?” Creators answered with neon nightmares, body horror, political rot, and fragile humanity — and those stories still feel eerily relevant today.

Image credit Madhouse